Out of a morbid curiosity, and a justified skepticism regarding the mainstream media's coverage of the horrid bombing and shooting rampage that took place in Oslo on Friday, I decided to take a look at the 1500 page manifesto of Norwegian terrorist Anders Behring Breivik, which he had apparently published online shortly before launching the attacks, and which can already be found on Wikipedia. I've not read the whole thing, but I have read the titles and introductory page(s) of all 200 some odd chapters, closely read through a few dozen individual chapters while skimming through many more, and conducted a number of searches for individual terms. I'm somewhat hesitant to publish anything on the matter, as one of the main goals of Breivik's attack was to spread his message. On the other hand, however, ignorance is neither bliss nor strength, and it behooves us to learn as much as we can about the enemies of human civilization.

It should go without saying, but since there are so many idiots on the internet, it must be stated outright that the present analysis of Brevik's manifesto and terrorist attack is in no way, shape or form, an endorsement of any aspect of it, but rather a modest contribution to the investigation of a previously unknown but extremely well developed terrorist ideology and, perhaps, a way to save others from the horrific tedium of parsing a madman's method. Reading through the work is truly an object lesson in the banality of evil.

After looking through the manifesto, I am tempted to argue that Breivik's act and ideology potentially represent something like a qualitative political transformation of modern fourth generation warfare, a dialectical response of the extreme right to radical left wing activism and Islamist terrorism. At this point, however, any such claim in that regard is premature to say the least.

The first thing we must recognize regarding Breivik's manifesto, entitled 2083 – A European Declaration of Independence, is that much of it was not written by Breivik himself. Indeed, the author does not call the work a manifesto, but rather a compendium. It contains historical sketches of medieval Christianity and Islam in addition to literary-style portraits of famous Crusaders from the middle ages as well as glosses on modern thinkers; it reprints manifestos of the Knights Templar from the middle ages; relays portions of academic articles on contemporary politics and the history of revolution; provides lengthy critiques of 20th century Marxist, feminist and post-structuralist theory; reprints news and media interviews and articles on everything from global Jihadism to demographic changes in Europe to everyday political opinion. It also relays blog-stlye articles by radical right commentators on multiculturalism, Marxism, Jihadism, immigration and so on. Many of these appear to be from Brevik's online associates and allies in the radical right blogosphere, but many of them seem to be by Brevik himself. The work contains hundreds if not thousands of individual citations.

In addition to these aspects of the work, there are also extensive diaries written while he was planning his attack, self-interviews, manifesto-style articles, and detailed operational plans. One can find, for instance, a detailed theory of what Brevik calls the ongoing "European civil war," a plan of action for taking the initiative in that war, a manifesto for a modern Knights Templar organization, lengthy reflections on military strategy and tactics, and innumerable tips for would-be radical right wing revolutionaries, including even lists of potential targets and projected budgets for various sorts of operations.

The work is broken up into three major sections. The first provides the history of a perceived civilizational struggle between western Christianity and Islam. The second lays out perceived problems of the contemporary political situation, which might be placed under the broad rubric of a perceived struggle between multiculturalism and monoculturalism in Europe. And the third provides a "solution" to these historical and contemporary problems in the form of three part plan for a European civil war.

If one takes the work at face value, it provides reasonable grounds for skepticism regarding the portrait of the killer that is slowly beginning to emerge in the international press. Media articles have referred to Breivik, for instance, as a Christian fundamentalist, a farmer and an avid video gamer. Breivik specifically mentions the importance of using video games as simulators for potential violent attacks – just as militaries do all over the world –, but he also suggests using a video game addiction as a cover for terrorist planning, as a way of explaining to friends and family why one is absent or not able to socialize for extended periods of time. Breivik was not a farmer, but he did found a business called GeoFarm that functioned as a front for him to acquire fertilizer for his bombs. This was not the only business front he appears to have founded. It appears likely, for instance, that he also founded a mineral mining corporation as a cover to acquire explosive materials such as TNT. One of the means by which he seems to have avoided detection was by founding these corporate fronts and acquiring materials sequentially rather than simultaneously.

I would also argue that it is probably wrong to label Breivik a Christian fundamentalist, at least as that term is normally understood. The bible is mentioned only 43 times in the work, and many of these references appear in discussions of Islam and the Koran. In a couple places he denies outright that he is a particularly "religious" person, while in others he states that he is "100% Christian." This tension underscores the fact that Christianity is, for Breivik, more part of his cultural identity than anything else. He plainly states that science should take precedence over biblical teachings in one of what appear to be several self-interviews. "As for the Church and science, it is essential that science takes an undisputed precedence over biblical teachings," he states to the imaginary interviewer.

To make some sense of Breivik's motivating ideology, it is probably more correct to employ the categories of traditionalism, nationalism and cultural conservatism. To this end, however, it is likely even more important to understand who Breivik considers to be the enemy. Analysts of Osama Bin Laden's Al Qaeda strategy often reference Bin Laden's identification of the "near enemy" and the "far enemy". For Bin Laden, the near enemy were local governments and states such as Saudi Arabia, while the far enemy was the United States and western civilization. A direct attack on one was at the same time an indirect attack on the other. Something similar can be said in the present case. For Breivik, Islam and global Jihadism are the far enemy while the proponents of multiculturalism, Marxism, socialism and political correctness in Europe and Norway are the near enemy. He sees the two as in collusion against European civilization in general and individual European national identities in particular. One might also add, in Breivik's case, a middle or median enemy between the other two, represented by the European Union, which he likens to the Soviet Union and dubs the EUSSR.

In this context, Breivik's terrorist attack against government buildings with the Labor Party in power as well as a summer camp for the party's youth wing, can be understood as a direct attack against the present and future of the mainstream Norwegian left as well as an indirect attack against the policy of multiculturalism typically promulgated by such groups throughout Europe. In the manifesto, Breivik rages against what he calls"Marxist/multiculturalist indoctrination campaigns".

Given the character of Breivik's attack, it is easy to understand why media sources were quick to suspect a group like Al Qaeda, which typically employs coordinated bombings and military assaults. However, Al Qaeda and associated groups seem, more often than not, to engage in coordinated bombings (Madrid, London) or coordinated assaults (Mumbai). When the two are used in conjunction, a bombing is often followed by ground assaults targeting rescuers at the first bombing (Iraq, Afghanistan), when rescuers are not simply targeted by another bombing.

Breivik's self-coordinated attack was somewhat different, however. The initial bombing created chaos and drew security forces to the area. But it was basically a military feint, providing him with cover to seek out his primary target, the Labor Party's youth camp, which he approached clad as a police officer supposedly securing the site in the aftermath of the bombing to draw a pool of victims into his immediate vicinity. The island provided his victims with no means of escape, and its isolation – in addition to the initial bombing – ensured a delay in the police response. The military precision of Breivik's self-coordinated attack is chilling. His manifesto contains detailed studies of ancient Chinese military strategy and tactics, Islamic and Islamist military strategy and tactics, and European leftist terrorist organizations and strategy, applying lessons learned for the purposes of waging fourth generation urban guerrilla warfare.

Above, I suggested that Breivik's attack potentially represents something like a qualitative political transformation of modern fourth generation warfare, a dialectical response of the extreme right to radical left wing activism and Islamist terrorism. To understand why this might be the case, we must take a few steps back. Breivik claims to be part of a Knights Templar group founded in 2002 with as many as ten other individuals from numerous European nations, who Breivik sees as modern crusaders against Islam and as the protectors of European and Christian cultural identity. The manifesto – written over the course of the last nine years as he worked out the details of his terrorist atrocity – contains detailed plans for the structure of the organization, as well as lengthy explanations of its motivations and goals. Given that the group was founded in early 2002, it makes sense to conclude that it was founded as a direct response to the rise of Osama Bin Laden and Al Qaeda's global Jihadist movement following the 9/11 attacks. In this way, the radical Islamist global "holy war" can be seen as a primary mediator for the foundation of Brevik's modern Knights Templar organization. Indeed, toward the end of his manifesto, Brevik predicts: "By September 11th, 2083, the third wave of Juhad will have been repelled and the cultural Marxist/multiculturalist hegemony in Western Europe will be shattered and lying in ruin, exactly 400 years after we won the Battle of Vienna on September 11th 1683."

The fact that Breivik claims to be part of a modern Knights Templar organization devoted to a military crusade against Muslims and Marxists will likely be put forward as evidence that he is a Christian fundamentalist. But this is probably not correct. Rather, if one is to believe the manifesto, the motivation behind the formation of the group was not Christianism per se, but rather traditionalism. Medieval military crusades led by groups such as the Knights Templar are framed in the manifesto as the traditional response of Christian Europe to threats against Christianity and European identity, and as such they are seen as the correct response to perceived contemporary threats against western Christianity and European identity.

Breivik advocates violence because he believes that there is no possible non-violent means of guarding traditional national identity and the values of what he calls cultural conservatism against multicultural Marxism and an influx of Muslim immigrants into Europe. Non-violent means are precluded, he argues in one section of the work, because Marxists and Muslims will soon constitute democratic majorities in nations across Europe. However, he does advocate non-violent means of resistance to sympathizers who are unwilling or unable to engage in violence. It is here that we see the influence of the radical left as a mediating factor for the foundation of Breivik's ideology.

He argues, for instance, that unlike the right, the radical European left's forms of organization have provided it with an influence far beyond its numbers. One single left wing activst, he writes, may be a member of dozens of groups and organizations, from anti-Fascist youth street gangs to anarchist groups, to media outlets, to professional organizations, mainstream advocacy groups and political parties. The result, he argues, is a political multiplier effect. In the compendium, he supplies plans for online networking, the organization of advocacy groups and political front organizations, suggestions on how to infiltrate and take over existing political organizations, how to distribute literature and so on, much of which is gleaned from the study of the post-'68 left in Europe. His hope appeared to be that his terrorist attack would spur such efforts on the right all across Europe.

Taking this proposed non-violent wing in conjunction with the Knights Templar military vanguard, one might well conclude that Breivik's terrorist action and manifesto represents a dialectical, right wing response to global Islamist terrorism and the radical left wing movement in Europe.

There is an interesting paradox at the heart of Breivik's work. He is a committed and avowed nationalist, but the scope of the work is not restricted by narrow nationalist concerns. It is not addressed to Norwegians, but rather to all Europeans, and right wing "cultural conservatives" in particular. As mentioned at the outset, it is entitled 2083 – A European Declaration of Independence. The declaration is clearly aimed at a double threat perceived by Breivik. On the one hand there is the threat posed to traditional European identity – which is equated with Europe's Christian heritage – by immigration from outside Europe, particularly on the part of Muslims from Islamic countries. On the other hand, there is the threat posed to individual national identities within Europe by the European Union and the cultural Marxist/socialist elite of individual nations, whose primary aim, he argues, is the "deconstruction of European and national identity".

Why 2083? Breivik predicts that what what he calls the European civil war between cultural Marxists and cultural conservatives will last until 2083, when the cultural conservative movement will finally prove victorious and stage a series of coups throughout Europe, instituting a culturally conservative political program that includes the re-institution of patriarchy, the unification of the Christian church (Breivik holds that the Protestant and Catholic Churches are bastions of cultural Marxism), the protection of national boundaries and the banishment of Muslims.

Breivik's first court appearance is scheduled for Monday. But it may well be the case that he has already determined his courtroom and judicial strategy. The compendium contains a number of chapters devoted to judicial strategy. Chapter 3.7 is entitled "Court/trial statements for Justiciar Knight and other patriotic resistance fighters after an operation." It begins: "These statements are meant to be used after a successful operation . . . A trial is an excellent opportunity and a well suited arean the Justiciar Knight can use to publicly renounce the authority of the EUSSR/USASSR hegemony and the specific cultural Marxist/multiculturalist regime." It continues a little later on: "By the time you are done presenting your demands, the judges and trial audience will probably laugh their asses off and mock you for being ridiculous. Nevertheless, it is important to ignore the ridicule and remain firm and focused."

It would be easy to simply dismiss someone like Breivik as a madman. We do so at our peril.

There is much more I could write on Breivik's manifesto and compendium, but this already is quite lengthy for a blog entry (even for me!), and I'm questioning whether to publish it at all. But I've already come this far. If anyone has specific questions about Breivik's ideology, I guess at this point I'm probably one of the few people who could hazard at least a semi-educated guess.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

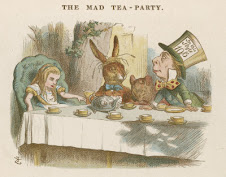

'It wasn't very civil of you to sit down without being invited,' said the March Hare. 'I didn't know it was your table,' said Alice, 'it's laid for a great many more than three.'

Third Party and Independent Opposition to the Two-Party State

Recent Posts

Subscribe

Search Poli-Tea

The Mad Tea Party

'It wasn't very civil of you to sit down without being invited,' said the March Hare. 'I didn't know it was your table,' said Alice, 'it's laid for a great many more than three.'

Contact

d.eris is damoneris at gmail

About

Eris is the largest dwarf planet, the Goddess of Discordianism and the muse of eristical dialectics.

Readers

Archive

- January (4)

- December (17)

- November (20)

- October (23)

- September (24)

- August (29)

- July (30)

- June (29)

- May (24)

- April (27)

- March (30)

- February (23)

- January (30)

- December (25)

- November (33)

- October (32)

- September (30)

- August (29)

- July (32)

- June (32)

- May (37)

- April (40)

- March (46)

- February (42)

- January (48)

- December (44)

- November (42)

- October (51)

- September (34)

- August (54)

- July (44)

- June (43)

- May (44)

- April (58)

- March (33)

- February (1)

Poli-Tea Parties

The Politeia Party

Info

- Article V

- Ballot Access News

- Center for a Stateless Society

- Fair Vote

- Free and Equal

- Free and Open Elections

- GNN

- Green Papers: Election Info

- Independent Political Report

- Independent Progressives

- Independent Voting

- Institute for Anarchist Studies

- Memeorandum

- OpEdNews

- Open Ballot Project

- Open Congress

- Open Debates

- Open Secrets

- Range Voting

- Rational Review

- Third Party and Independent Daily

- Uncovered Politics

- VOID

- Vote Out Incumbents

A Poli-Tea Media Project

Blogs

A Poli-Tea Politics Project

Categories

- 2010

- 2012

- action alert

- administrative

- AK

- AL

- anarchism

- anti-incumbency

- apologetics

- argument

- AZ

- bailouts

- ballot access

- bias

- bipartisanship

- C/R politics project

- CA

- campaign finance

- candidates 2010

- cartoons

- censorship

- CO

- collusion

- conspiracy theory

- Constitution Party

- continuity

- convergence

- corporatism

- crisis

- CT

- delusion

- democracy

- demythification

- dialectics

- digest

- discontent

- election law

- exclusion

- FL

- fusion

- GA

- Greens

- guest posts

- historical

- ID

- ideology

- IL

- IN

- independence

- indoctrination

- indypedia

- infiltration

- international

- IRV

- KS

- KY

- lesser evilism

- Libertarian

- local

- MA

- MA 01/10

- mandatory minimums

- MD

- ME

- media

- messianism

- MI

- MN

- moderates

- NC

- NJ

- NJ Gov 09

- NM

- NY

- NY's 23rd

- OH

- OK

- one-party state

- open debates

- opportunism

- OR

- PA

- Pirate

- police state

- polling

- populism

- prediction

- primary follies

- profiles

- progressive

- propaganda

- proportional representation

- protest

- redistricting

- Reform Party

- religion

- RI

- RV

- SC

- scandal

- scholarship

- SD

- socialism

- Socialist

- states

- strategy

- surveillance

- tea party

- term limits

- third party blogosphere

- third party daily

- third party tea party

- TN

- turnout

- twin evils

- TX

- UK

- UT

- Utah

- VA

- Vermont

- viability

- violence

- voting

- VT

- WA

- wake up call

- war on drugs

- WFP

- Whigs

- WI

- WV

8 comments:

Interesting. Can I assume that Breivik is Catholic from his focus on the Templars? If so, there's even less cause to call him "fundamentalist" in the usual literalist sense of the word. Since his lawyer has already said that Breivik will explain himself on Monday, I assume that he surrendered exactly so he would be able to address a global audience. I've equated him with Timothy McVeigh on the basis of methodology, but Breivik may be more like the Unabomber in using violence to force the world to pay attention to him.

"Can I assume that Breivik is Catholic from his focus on the Templars?"

I'd say you could call him a small "c" catholic, in the sense that 'catholic' means universal, since he wants to see a unified and reformed Christian church in Europe. In one of the self-interviews toward the end of the text, which I quoted a bit from above, he writes: "My parents, being rather secular wanted to give me the choice in regards to religion. At the age of 15 I chose to be baptised and confirmed in the Norwegian State Church [which is Lutheran]. I consider myself to be 100% Christian. However, I strongly object to the current suicidal path of the Catholic Church but especially the Protestant Church." (p. 1403.)

There's a section where he talks about the importance of a single pope who will represents the unity of the Christian church in the future utopian state he seeks. Media reports I;ve read have stated that he converted to Catholicism from Lutheranism, but I haven't seen any direct evidence of that in the book, though I haven't closely read large portions of it.

What's interesting to point out is his pick of target (The Norwegian Labour party) to strike at "leftism". The Labour party of Norway hasn't really been "left wing" for quite some time. It's over the past 5 or 6 decades where it's had a near monopoly on power in Norwegian politics drifted to centrist to centre right politics, pretty much abandoning left wing politics, kind of like the Democratic Party of the US. (Though in comparison to US politics, it'd be "far left"). Apparently there's a historical basis for this too, where they abandoned a planned economy in their platform in 1948, in return for the marshall aid.

Just thought I'd bring that tidbit up.

In the manifesto, Breivik talks about what he calls his "crossroads" period around 2003, when he was still involved with electoral politics and before he decided to fully convert to the dark side. He was active in the right wing populist Progress Party, and says he ran for city council in Oslo under their banner. He concluded at some point that they were part of the problem, and that even if there were reasons for optimism regarding their outlook (widespread support among the people), they would be ridiculed and marginalized by the Marxist media-political conspiracy.

Those pesky Marxist media-political conspirators, always putting the white man down!

"I'd say you could call him a small "c" catholic, in the sense that 'catholic' means universal, since he wants to see a unified and reformed Christian church in Europe"

At the risk of evoking Godwin's law, didn't Hitler also strive for that, at least in the German speaking states?

I'm not sure about Hitler's ideas regarding the establishment or unification of the Christian church. But if there is ever an appropriate time to make a comparison with Hitler, it's an a discussion of Breivik.

Sam brings up the comparison with McVeigh, but I'd argue that even with their similarities, Breivik is qualitatively different if only because of the manifesto and his well developed terrorist ideology.

Breivik is more like McVeigh plus Pierce who wrote the Turner Diaries which inspired McVeigh, plus the Unabomber (whose work Breivik excerpts in his manifesto) and Hitler because of Breivik's long range vision and plan. I might even go so far as to claim that Breivik is beyond Hitler, given his account and critique of Nazism. You could probably make a convincing argument that Breivik's compendium makes Mein Kampf look like the work of an amateur or dilettante.

This article has been added to the repository Analyzing Breivik's manifesto

.

Post a Comment