At

The Moral Liberal, Jack Kerwick makes the case for the political independence of the tea party movement from the political opportunists in the GOP, and debunks two common arguments against third party activism and advocacy. Excerpt:

If and when those conservatives and libertarians who compose the bulk of the Tea Party, decide that the Republican establishment has yet to learn the lessons of ’06 and ’08, choose to follow through with their promise [to form a third party], they will invariably be met by Republicans with two distinct by interrelated objections.

First, they will be told that they are utopian, “purists” foolishly holding out for an “ideal” candidate. Second, because virtually all members of the Tea Party would have otherwise voted Republican if not for this new third party, they will be castigated for essentially giving elections away to Democrats. Both of these criticisms are, at best, misplaced; at worst, they are just disingenuous. At any rate, they are easily answerable.

Let’s begin with the argument against “purism.” To this line, two replies are in the coming. No one, as far as I have ever been able to determine, refuses to vote for anyone who isn’t an ideal candidate. Ideal candidates, by definition, don’t exist. This, after all, is what makes them ideal. This counter-objection alone suffices to expose the argument of the Anti-Purist as so much counterfeit. But there is another consideration that militates decisively against it.

A Tea Partier who refrains from voting for a Republican candidate who shares few if any of his beliefs can no more be accused of holding out for an ideal candidate than can someone who refuses to marry a person with whom he has little to anything in common be accused of holding out for an ideal spouse. In other words, the object of the argument against purism is the most glaring of straw men: “I will not vote for a thoroughly flawed candidate” is one thing; “I will only vote for a perfect candidate” is something else entirely.

As for the second objection against the Tea Partier’s rejection of those Republican candidates who eschew his values and convictions, it can be dispensed with just as effortlessly as the first.

Every election season—and at no time more so than this past season—Republicans pledge to “reform Washington,” “trim down” the federal government, and so forth. Once, however, they get elected and they conduct themselves with none of the confidence and enthusiasm with which they expressed themselves on the campaign trail, those who placed them in office are treated to one lecture after the other on the need for “compromise” and “patience.”

Well, when the Tea Partier’s impatience with establishment Republican candidates intimates a Democratic victory, he can use this same line of reasoning against his Republican critics. My dislike for the Democratic Party is second to none, he can insist. But in order to advance in the long run my conservative or Constitutionalist values, it may be necessary to compromise some in the short term.

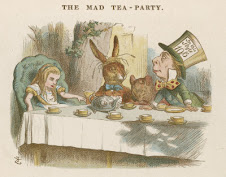

Read the whole thing. Before the tea party movement was hijacked by Republican party hacks, there was a moment at which it appeared to hold the promise of a real movement for political independence from the misrule of the Republican and Democratic parties. This latent possibility remains, and, the longer self-described tea party activists continue to demonstrate a slavish allegiance to the Republican party, the greater will be the contradiction between the so-called "tea party movement" and its historical forebears in the American revolution. The Boston Tea Party, after all, was part of a radical movement for

political independence from an unrepresentative and tyrannical government. How do we save the legacy of the Boston Tea Party from today's

Tea Party Tories?

3 comments:

This tempts me to repeat my comment from yesterday re: the New Progressives, but I see that Berwick takes a different but familiar approach to the problem of the ideological enemy. Citing Glenn Beck's comments on the 2008 election, he takes the Leninist view that the ideological enemy's victory would be preferable to the victory of a tepid or inadequate ally if it forces a crisis that results in the desired political awakening. This approach has little chance of swaying conservatives who, being conservative, don't want to see a crisis and don't share Berwick's presumed confidence that Right will prevail. So like the progressives, the TPs must learn not to fear the ideological enemy. Once they don't have to worry about the worst case, they can concentrate on promoting the best option.

I was actually thinking about your comment from yesterday as I was writing up this post, since Kerwick specifically addresses one of the issues you brought up there, i.e. how to address the issue of the greater/lesser evil.

"like the progressives, the TPs must learn not to fear the ideological enemy"

One way to learn this lesson, perhaps, would be for strategic/tactical alliances between TPs and progressives against their common enemies in the Democrat-Republican two-party state. Such alliances can be found already at the margins of the Republican and Democratic parties. The recent vote on the Patriot Act passed with overwhelming bipartisan support 74-8. It is noteworthy though that the 8 vote opposition was, in a way, broader: encompassing an Independent, progressive Democrats, and libertarian-leaning Republicans.

D.eris,

There's been an attempt in Maine to start an alliance of sorts between Greens and Libertarians, though I'm not yet as sure how successful it's been thus far. Worth checking out though.

Post a Comment